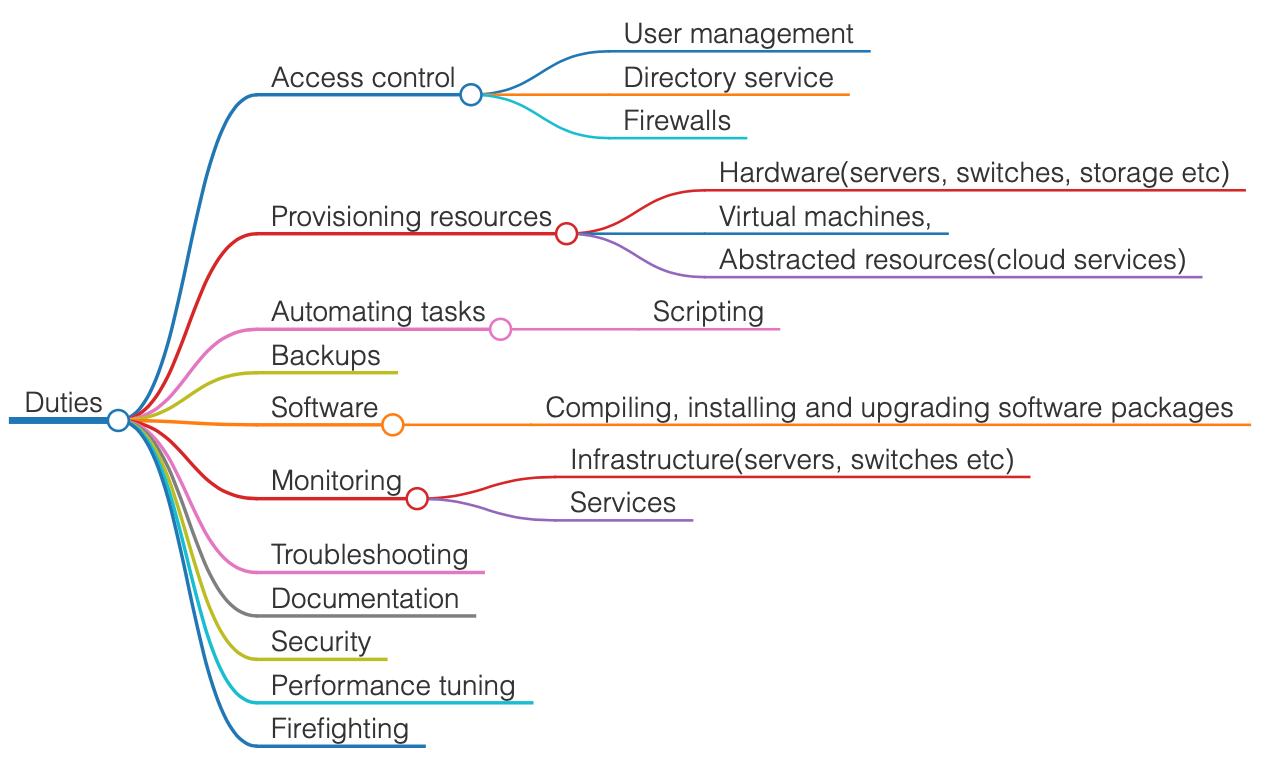

Role of a Sysadmin

A sysadmin is responsible for upkeep, configuration, and reliable operation of systems and services.

Duties

Accidental sysadmin

I was living in Raleigh, North Carolina, working as a Performance Engineer when I decided to move to Denmark to be with my then girlfriend, now wife, and start a family. Moving to another continent entails a lot of change and looking for a job is no different. I learned soon that finding a job as a Performance Engineer in Europe is not as straightforward as it would be in the US. I instead ventured on a job search based on the skills I have. Voila, I found that I could be a starter sysadmin - I have administered systems before, and turns out there is a lot of commonality between "understanding the system enough to engineer its performance" and "administering a system".

After some Skype interviews, and arduous work permit paper work, here I am in Aarhus, Denmark.

My personal experience as sysadmin

Orientation

Orientation or transition is very important for a sysadmin is very important, particularly so for someone who is in those shoes anew. Here are some observations I made on the first day in the job :

-

My predecessor had left the job a few months before my arrival

-

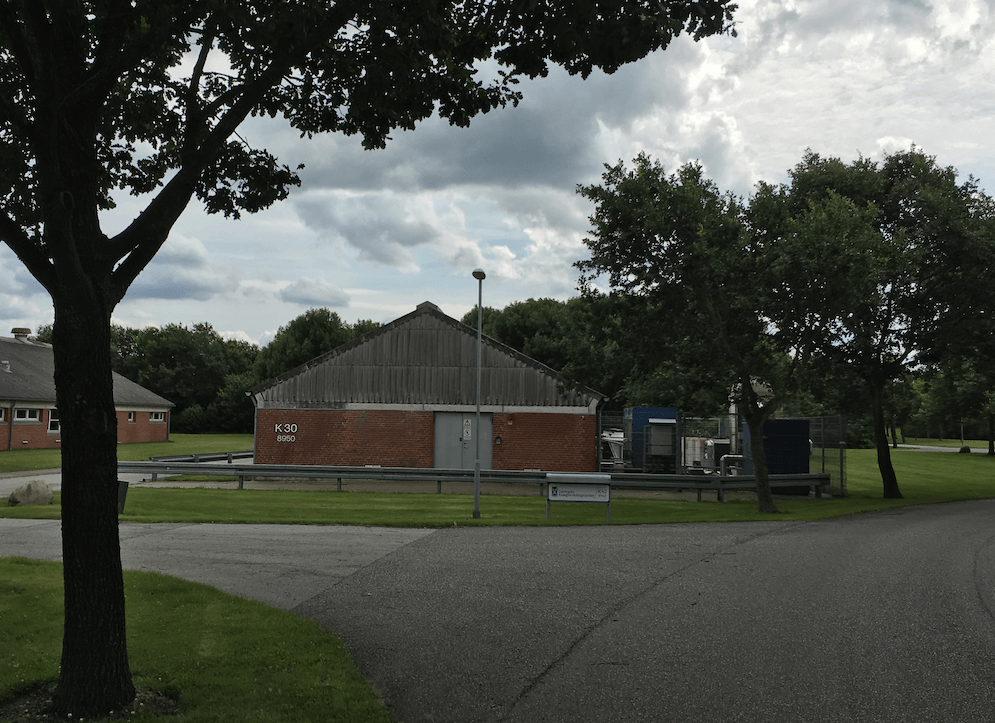

A barn is re-purposed as a capable data center

-

There is no documentation whatsoever about inventory or purpose of the machines

-

The HPC batch scheduler system currently in use (PBS) is causing a lot of pain

-

All of my colleagues are bioinformaticians/researchers except one who had been a sysadmin early in his career

-

All of my colleagues are nice to me and are rooting for me to do a great job

-

I have a lot of room to do good and learn

So, I buckled up and started the ride.

Reconnaissance

Before I began, I needed to explore and understand what makes up this cluster and what I should be dealing with. Given the lack of documentation, I had to do the reconnaissance on my own. Here is how I went about it..

nmap - scan the network(s) to determine which hosts are online, what services they offer(web, database, DNS, firewall etc), which operating system versions are they at, ports open in them and more.

This resulted in an Excel document that I treated as an inventory from then on.

Next up, DNS records. Once I found out which servers are providing name resolution, I looked at their records to get a list of all services that could be in use by others. My Excel doc was made slightly better and richer with information.

Next, searched for a centralised syslog somewhere, and realised there isnt one.

Moving on, users and groups. Another result of the network probe was the NIS server that was acting as the identity provider. So, logged in there, and grabbed the list of users and groups. With the help of senior colleagues and some common sense poking around, I made notes of who uses the system, and the purpose of the groups. I had never worked with NIS before, and made note of it being a pain point.

Cron jobs : One of the conversations with users of the systems pointed to some cron jobs that happen in the cluster. So, I listed crontab on all machines and obtained information about the cron jobs that were to be cared for.

An advantage of a controlled private cluster such as this one is that you can probe the entrypoint and understand which users can get how far. Since the primary interface to the clsuter was via SSH, I probed the sshd_config files to see who has access to go where.

Know when to give up

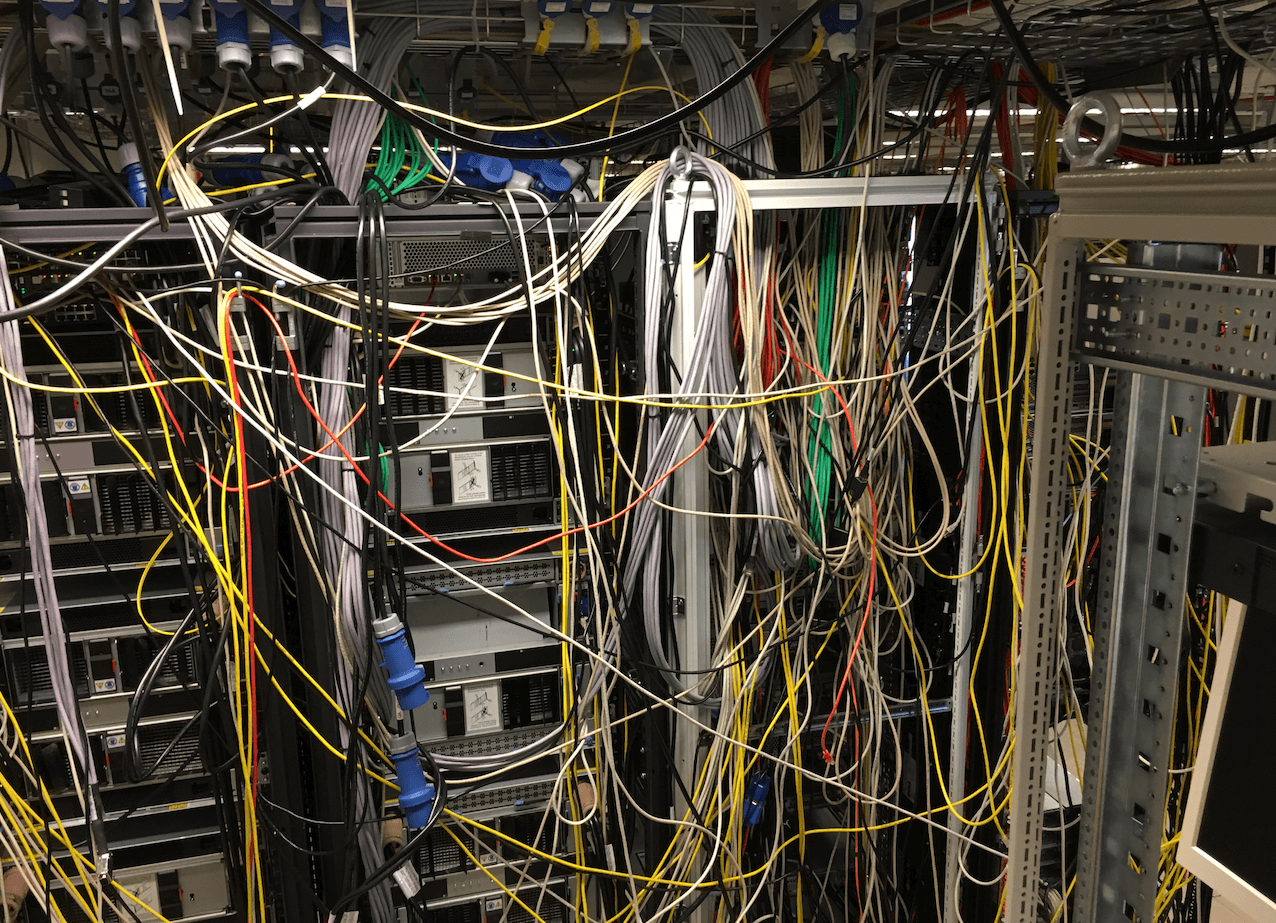

At this point, the facts I learned during reconnaissance made me very uncomfortable to think about upkeeping this setup. There was so much technical debt on this setup that reinvigorating it would be like putting lipstick on a pig.

-

Primary DNS server was an intel Pentium III server that must have been atleast 14 years old.

-

Some of the compute nodes are so old that they could not run recent versions of operating system. This holds back the entire cluster from moving on.

-

The job scheduling system keeps crashing because user memory limits could not be enforced.

-

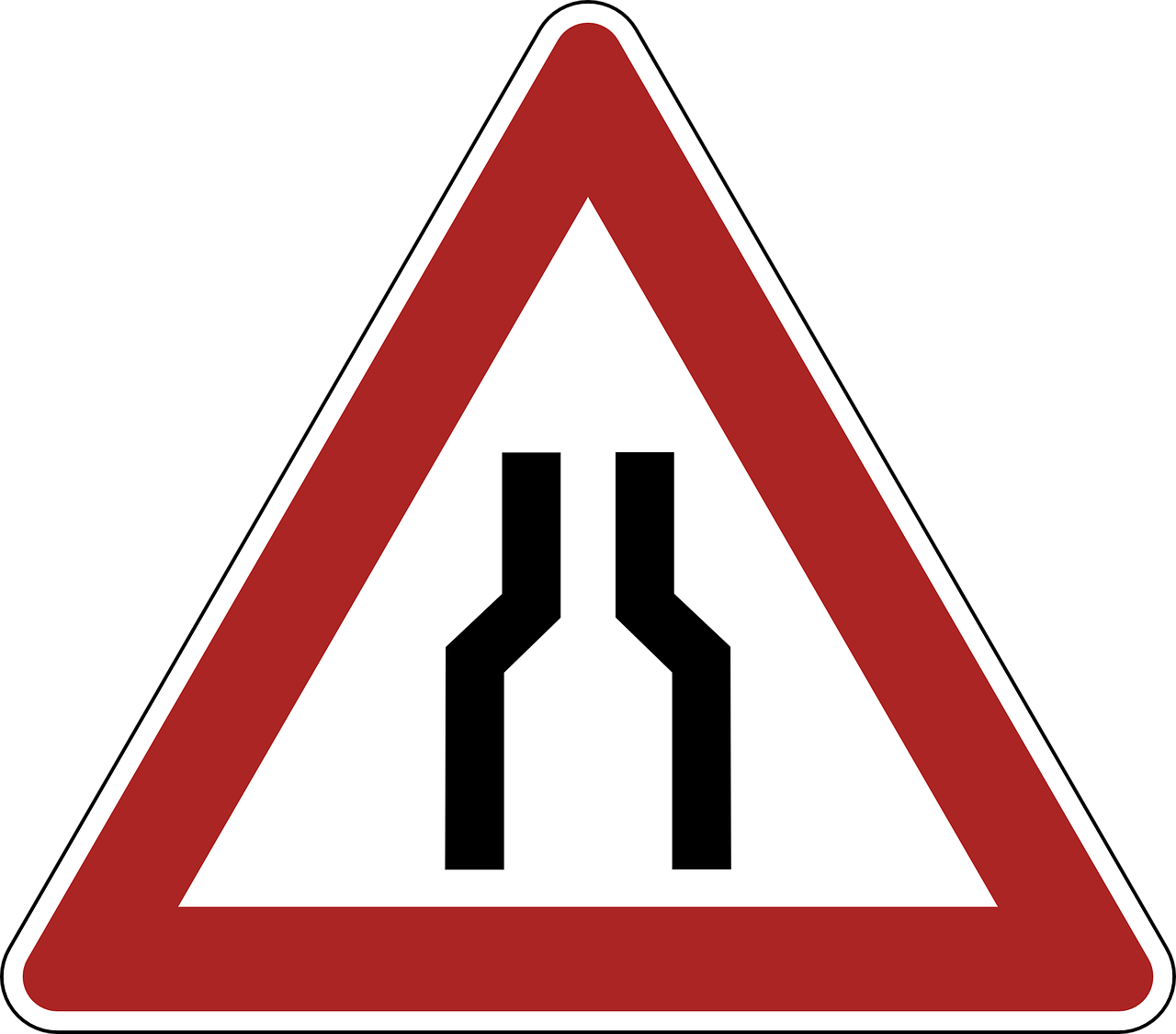

Network to the storage servers were clearly the bottleneck. Single 1 Gigabit pipe for all compute nodes <-> Storage.

-

Lack of documentation

So, I had the conversation with boss. This cannot go on with 'maintenance'. We need to plan for a new cluster and move to it and leave the burden behind. He agrees.

We decide to take a cautious 'parallel worlds' approach. I would keep oiling this old setup until the new setup is built up, tested by a few beta users, and is declared ready for operation.

Transitions like this are never easy. I needed to do a lot of thinking to make sure I know what I am doing, and that users will have enough information and guidance on their hands when they make the move.

✨ GHPC ✨

The hardest problem first - naming the new cluster!

I settled on GHPC - short for [Global | Genetics | Genomics] High Performance Compute cluster. Pretty smart eh?

Before embarking on the architecture of the new GHPC, I decided it needed to incorporate :

-

Infrastructure as code - All nodes must be provisioned via PXE boot and simply get to their service level by running an Ansible playbook. Any modifications to that service has to occur in an idempotent fashion via the playbooks.

-

Separation of concerns - Infrastructure services are too important to tolerate influence from other services. They needed to run as independent as possible - Storage server going down should not impact identity servers, DNS servers etc. DNS server going down should not impact access to storage for compute nodes etc.

-

Automation - Anything that can be automated should be automated. An admin's toil should be reduced deciding which automated script to run to fix what.

-

Keep it Simple - Prefer simple and effective tools that does one thing well over fancy cool choices that pimp up your CV and cause tech burden.

Hardware - what to buy?

Meticulous selection of hardware and their setup plays a key role in HPC clusters where every bit of performance counts and often makes the difference in how many days/weeks a user's job takes.

It is not as easy or straightforward as one might think. The servers with CPUs containing fastest cores or most number of cores, most amount of memory, fastest SSDs doesnt mean they are fit for the work. HPC applications often come with their own unique needs. The role of the person choosing the hardware is to carefully study the needs of the applications that will eventually run on this hardware and how well to satisfy those needs under the given conditions including the monetary limits.

To really understand our need, I set out to get a sample of workloads that are often run in the cluster and ran tests with them.

I have one cluster of workloads that are purely CPU and memory bandwidth bound. Another cluster of simpler workloads that are mostly IO bound and could not care less about the CPU and memory.

The above insights made me take a two-pronged approach :

-

Special purpose hardware optimised for high impact workloads

-

Cost optimised hardware for general purpose workloads

I learned quite a lot about systems design, limits, bottlenecks and practiced the art of trading off one for another.

Below are just some examples of the motivations behind hardware purchase decisions. There are several other decisions I had to make, but I will keep their rationale for another detailed post.

-

Intel Xeon based servers (because we are stuck with the intel compiler for business reasons, and AMD processors doesnt bode well with this situation even if they are arguably better)

-

Hyperthreading will be turned ON in some servers that service IO bound workloads, while turned OFF in some servers that service workloads that are purely compute bound with little opportunity to make use of HT.

-

Some of our workloads are legacy software still bound to a single core. So, we need cpus with faster cores and not many slower cores.

-

Most of the jobs make use of local disk to perform their work and copy their output over to central storage upon completion. Using SSDs instead of spinning disks for local storage is a no-brainer.

-

As much as we would love to have the lower latencies offered by the SFP+ transceivers and optical fiber networking, we decided on cheaper 10G Base-T networking as a "good enough" choice.

Figuring out what hardware to buy may be fascinating, but the process to procure them, navigating the rules and regulations at a public institution is obviously not. I sought help and was fortunate with senior colleagues and they helped move things through.

HPC hardware demands a lot more than say building a PC for personal use. Among other things you have to take the following into account as well. Rack space (and how deep they are), power requirements (I needed a 16A outlet while only 10A outlets were nearby), cooling requirements (hot aisle/cold aisle setup, air flow), being social enough and have enough goodwill to get help from colleagues to lift and fit these servers in the racks, and so on.

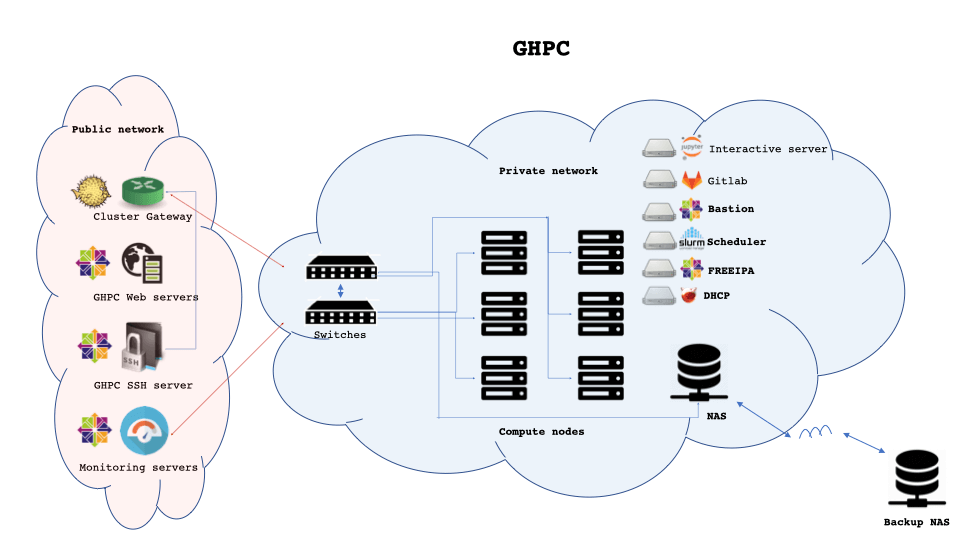

GHPC Architecture

I had the golden opportunity to build a cluster from scratch. Doing things right means I will have an easier time maintaining the cluster once it is operational.

There is definitely more to architecting a HPC cluster than what I can condense into this long blog post. However, I will give you a brief view of my choices and how they make up GHPC.

Choices

-

All compute nodes are identical software wise. They are provisioned via an Ansible playbook. A new compute node can be added in less than 4 minutes.

-

Networking for this cluster is very simple - two "top of the rack" 10G leaf switches that talk to storage(NAS) via redundant 40G links.

-

Simple switched IP network = All nodes can talk see/talk to each other. Good enough for our scale.

-

Internal network stays strictly private - all communications in/out to this network from outside flows through "Cluster gateway" - an OpenBSD server running pf serving as a firewall.

-

Centralised identity provider - Replicated FreeIPA servers act as the identity provider. It also provides LDAP auth for internal services like Gitlab, Jupyterlab etc.

-

SSH and SFTP are primary interfaces to interact with cluster from outside. SSH access is by key only - NO PASSWORDS. Accessing the SSH server from outside the institution requires second factor authentication(2FA) using Duo.

-

Internal services are only available in private networks. Users are expected to SSH tunnel using their identities to access services like gitlab and jupyterlab.

-

Infrastructure services like FreeIPA, web servers, slurm controller etc are run virtualised using KVM - makes it easy to snapshot and backup. It also facilitates simply running them on a different host should any physical servers crash.

-

Batch job scheduling is taken care of by SLURM - the defacto scheduler in the HPC space.

-

Web servers are intentionally isolated from being able to access the cluster network as a safety measure. Access to web servers are strictly guarded - separate SSH keys other than the ones being used for the cluster. Access only on a need basis using locally stored SSH keys.

-

Primary storage for the cluster are a bunch of custom built ZFS servers (FreeBSD and Linux). Refer to my other posts for how I built them.

-

Storage access is provided via simple NFS v3 - it works great, and can even saturate the network pipes upon demand.

-

The primary storage servers are backed up/mirrored using simple automated rsync to a secondary NAS at a different location using dedicated fiber. Note: Simple as it is, it works for us under the assumption that backup will only be used for DR and not business continuity. We expect downtime if the primary storage goes down hard.

-

Monitoring - Time series metrics collected from all nodes and services by Prometheus and visualised by Grafana. rsyslog pipes logs to a central syslog server for audit purposes. Filebeats ship logs to a single-node ElasticSearch setup for centralised log analysis.

-

All compute nodes have mitigations turned OFF! - these are private compute nodes that strictly run software from local repos. that extra 10-30% of performance penalty for these mitigations are not worth it here. If untrusted code is run on these machines, I have a bigger problem to deal with than these vulnerabilities.

-

Redundant Unbound on OpenBSD works as Authoritative, validating, recursive caching DNS servers.

-

There are other services like database servers (PostgreSQL and IBM DB2) that are left out of the discussion to keep scope manageable.

Performing my duties

So, how do I perform the duties of a sysadmin now?

After all, a sysadmin's job is "upkeep, configuration and ensure reliable operation".

Upkeep:

Goal is to keep GHPC alive/up reasonably. I have my alerts set up before something blows up - example: 'disk is 80% full' and for obvious problems such as "node - sky001 is unreachable". These alerts and "system service requests" take highest priority in my to-do list.

I spend a reasonable amount of time thinking about why it occurred, collect relevant logs and bring it back to expected service as soon as possible. Some times, that means SSH ing into nodes to figure out and then running an Ansible playbook from controller to fix things, and other times it could be a hard reset on the node and re-provisioning it with Ansible.

If the situation is a hardware failure, it simply results in a warranty request, and wait status until the parts arrive.

Configuration:

Most services need configuration to become useful to users. All configuration files and scipts to trigger the configuration exists in Git repositories under sysadmin's thumb. Configuration changes occur only via Ansible Playbooks that change things idempotently so that if I ever were to re-build this service on another hardware, it would simply be an "ansible-playbook something.yml".

Reliable operation:

Reliability means the consistency of the system in performing its required functions in its context over time. I respect the need for consistency and believe change for the sake of change is not worth doing - A lot of CI/CD folks would probably balk at me saying this, but that argument is for another blog post.

I simply refer to the idea that users expect a certain level of dependability on the state of the system. I try best to not do "pull the rug" changes. Example : A new version of software is made available as xyz-1.02 and xyz-current is sym linked to the latest version. This way, if a user referred to a specific version they will not be impact by my upgrading the tool they use.

Design decisions are made with least interruption to current state of affairs. Example: if I bring the central NAS down for maintenance too often, long running jobs would just be restarting again and again wasting precious resources. So, as sysadmin, I do my darned best to keep the system operational and in correct state during normal operation. That does not mean we resist change - simpler configuration changes happen continously, and disruptive changes/upgrades are thoughtfully deferred for our annual planned maintenance where jobs are paused with months' notice.

Continous automation:

Simple tasks such as permission changes, file transfers, batch job management etc are all automated using Bash or Python scripts. If the state of compute nodes or infrastructure nodes needs changing, then Ansible takes over.

Compiling software for performance:

A surprising proportion of my time goes towards maintaining our software repository with tools compiled in way that is best for our hardware. Some scientific software are compiled with Intel compiler as per author's instructions - with double digit performance improvements over standard compiles. Most other tools are simply compiled with -march=native on our hardware.

Performance engineering:

The amount of difference one can make by simply focussing on these key areas is astounding :

- Choosing the right data structures and algorithms to work with

- Removing obvious bottlenecks in processing

- Organising work around resources

General purpose devices and services often need tailoring for purpose. Simple to say, but takes a whole lot more than I can condense into this subsection. You can look into how I analysed one of our ZFS file servers' performance to get an idea about what goes in here.

Performance troubleshooting:

Another aspect of performance engineering that I get summoned upon is from the user end of it - "My job takes 7 days but 'I need it faster' or 'it took less time last time around'" etc. This involves performance analysis and often leads down the rabbit hole to find that simple solution.

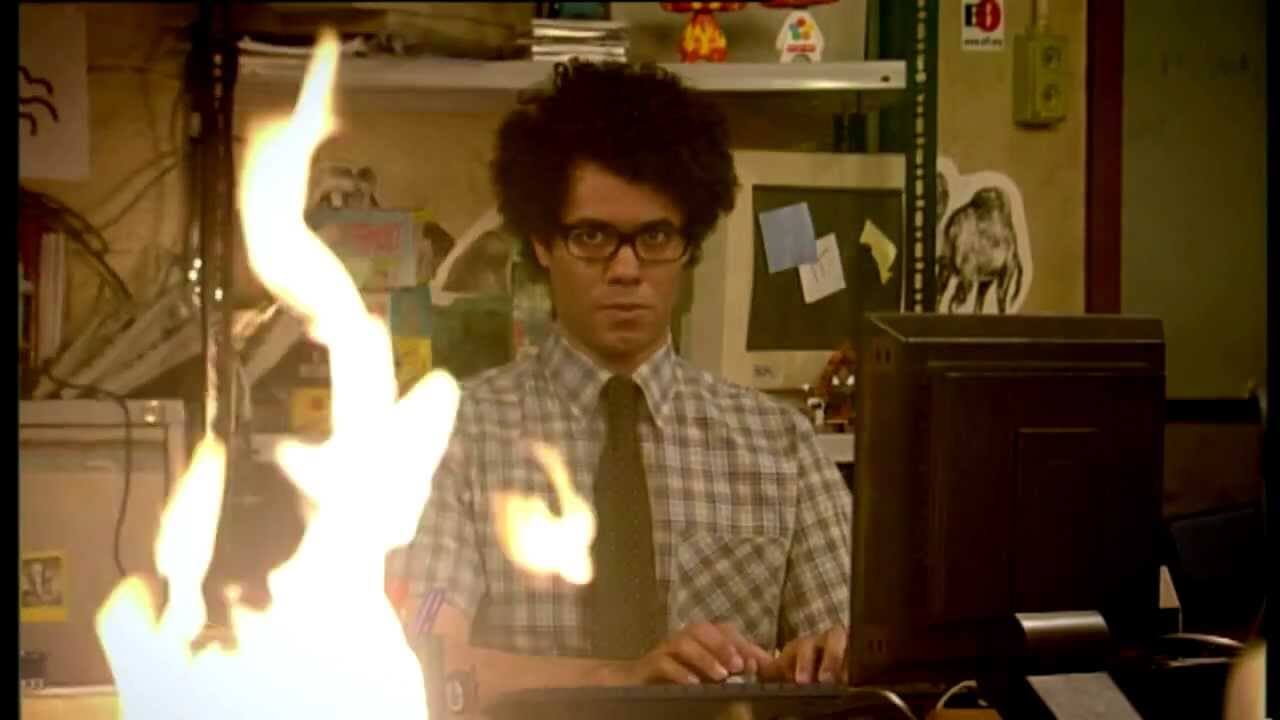

Fire-fighting:

Yet another duty of a sysadmin is to deal with "firefight"s - expected to solve issues before they wreak havoc. You know you got into one when you get emails in the lines of "Something happened, and my files are gone. Pls help!".

This is the most demanding yet most satisfying aspect of the job. It makes you sweat and also give you war stories to learn from and reminesce at your future job interview. Here are some examples of fires I have put off :

-

User says - "I have files that re created in the future in my home directory" :- NTP server was down and Chrony failed ot sync.

-

Some users can login while others cannot - IPA server not reachable and cached SSSD credentials let some users log in.

-

File server has reduced capacity - Two disks have failed in NAS, and unfortunately in the same RAIDZ2 VDEV. Rush to get hardware replaced and initiate scrub.

-

SSH login takes too long for users - NFS servers serving locations in user's $PATH are not reachable.

-

Oh DNS..... the tricky monster that causes problems sometimes rightaway or at times lead to a slow-motion disaster.

-

Firewall changes with pf - locking oneself out, or blocking something that we didnt know was being used.

-

"kinit admin" fails with "Credentials revoked" - Too many failed attempts for user admin on FreeIPA. Get to work with ldapmodify.

-

Systemd - oh my! - It is hard to not to cuss in front of colleagues when dealing with a systemd induced madness. This is one anti-unix tool that aspires to "Do everything in a needlessly complex and unintuitive way".

Continous monitoring - "on call":

Monitoring is a key aspect of a sysadmin's job. Keeping an eye on what is going on and catching problems early saves a lot of headache later on. Having the data available helps with root cause analysis and audit purposes. When you are in a firefight, having monitoring systems functional makes a big positive difference. Monitoring done right is an art and science which cannot be condensed into a subsection. It deserves a detailed post for itself.

I have Prometheus alertmanager set up to catch known common sense issues before they cause trouble. For those other problems that I end up solving manually, the EK(ElasticSearch + Kibana) tool comes in handy to query centralised logs easily and understand what went on and identify the root cause. Such manual interventions often end up adding more alert patterns to my monitoring systems.

Continously improving documentation:

As a sysadmin, I keep two kinds of documentation:

-

User guide - for users of the system, so that users know how, what, where and why around the cluster. Made as clear as possible with loads of screenshots and verbose explanations of services and guidelines. Example - GHPC wiki/userguide

-

Admin handbook - "The book" expected to be used only by a superuser/admin. This guide has intricate details of the system, commands used to perform actions, notes from issues, post-mortem analysis notes, network diagrams, hardware details, admin workflows and many more. This guide is expected to be passed over to the next sysadmin or whoever takes over in a "hit by the bus" scenario.

Necessary skills

-

Enthusiasm for this line of work.

-

Problem solving skills - focus on the big picture, then drill down to details.

-

Know where to look for information to solve a problem.

-

Able to automate all repetetive tasks.

-

Document, monitor, log, audit everything.

-

Ability to describe technical information in easy-to-understand terms.

-

Patience.

Tools

- nmap - utility for network discovery and security auditing

- cronguru - helper utility to write cron tasks

- mdbook - A static docs site generator written in Rust

- unbound DNS

- FreeIPA - Centralised identity solution

- Ansible - Automation tool

- rsync - file copying tool with delata transfers

- Duo - Multi-factor authentication for SSH

- Slurm - batch job scheduling system

- Prometheus - Pull-based time series data monitoring system

- Grafana - Data visualisation tool to chart data in Prometheus and other sources

- ElasticSearch - search engine to provide full text search on logs

- Filebeat - Lightweight log shipper for Elastic Search

- Kibana - visualisation tool for working with logs on ElasticSearch

- CentOS 8 - popular RHEL based Linux distribution

- FreeBSD - popular unix based operating system with deep ZFS integration

- ZFS - A copy-on-write(COW) filesystem

Resources

Idempotence is not a medical condition

Hyperthreading - where each physical CPU core appears as two logical cores to the OS

Conclusion

So, this is how I work as a sysadmin. If you made it this far in a long post, I hope you enjoyed reading it, and learned a thing or two. If you have any corrections, suggestions on this post, contact me. If you'd like to work with me or hire me for my next job, please write me a note :-)